Goya Francisco

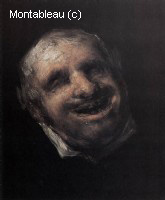

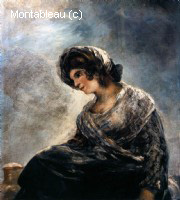

Excerpted from "About Modern Art", by David Sylvester "Goya's portrait of himself being nursed by his physician is inscribed: 'Goya in gratitude to his friend Arrieta for the skill and care with which he saved his life in his acute and dangerous illness suffered at the end of the year 1819 at the age of 73. He painted it in 1820.' Goya otherwise celebrated his rescue from the jaws of death by decorating the walls of his villa, the Quinta del Sordo, with the fourteen 'black paintings', which by and large are the most sickening images he ever painted. Having survived, he not only gave himself to realising hellish visions, but chose to do so in a form that left him surrounded by them (and without the freedom canvases would have offered to turn their faces to the wall). "All sense of relief was reserved for the Self-Portrait with Dr Arrieta. It almost resembles a Pieta. Goya is seen sitting up in bed, more dead than alive, leaning back against the doctor, who supports the patient's weight with one arm and with the other raises a glass of medicine towards his lips. Portrayals such as this of love or warmth between human beings are rare among Goya's mature works. Others have created images as terrible as his of man's inhumanity to man, but no other major artist has conceived of a world so comprehensively consumed by hate. "Goya seems to have come to take it for granted that a human being with power or authority over another will abuse it to ruin the other to dismember, deprave, despoil, relentlessly, gratuitously. Maybe the scenes in The Disasters of War of the pointless butchery which the victors inflict on the vanquished tell us no more about Goya himself than that, like any humane and rational being, he loathed the excesses of war. Maybe the scenes in the Caprices in which the old sell or corrupt their charges tell us no more about him than that he was a sharp social satirist. His witches' sabbaths where babies and foetuses are roasted are not proof that he assumed, even unconsciously, that all women would rather eat than feed children. But there can be no doubt as to the depth of his despair in the face of his guarded inscription on a drawing in the Prado of an attractive young woman seated cuddling a small child: 'She seems to be a good woman.' Love is exceptional. Depictions of tenderness and compassion are found among the famine scenes of the Disasters: love flowers in the context of deprivation. A loving care is portrayed in the painting made in 119 of The Last Communion of Sanjoside Calasanz. It is curiously prophetic of the Self-Portrait with Dr Arrieta - both are images of a suffering man sustained by a man who is feeding him. "The mouth plays a role in Goya's art more prominent than in that of any other major artist. Mouths leer, grin, gape, gasp, moan, shriek, belch. A hanged man's mouth lies open and a woman reaches up to filch his teeth. Grown men stick fingers in their mouths like sucking infants. Mouths vomit, the sick gushing out of them, and a great furry beast sicks up a pile of human bodies. Mouths guzzle: they guzzle avidly, ferociously, living flesh as well as dead. Saturn grips one of his children in his fists and with his mouth tears him limb from limb. "In Rubens's version (which Goya would have seen in Madrid), Saturn bends his head over the body, sinks his teeth in the flesh and sucks the spurting blood of his kicking, screaming child. Goya's version shows a bleeding remnant of a body, one of its stumps entering the hoary giant's gaping mouth. Goya's painting of an episode from the sixteenth-century novel El Lazarillo de Tormes is its comic counterpart. The blind old man, wanting to smell out whether his supper has been eaten by the youth Lazarillo, 'forced open my mouth with his hand, and thrust in his nose, which was long and thin, and at the same time had grown another few inches with rage'. 'Those who reach eighty,' reads one of the Caprices commentaries, 'suck little children; those under eighteen suck grown ups. It seems that man is born and lives to have the substance sucked out of him.' "And mouths are focal points in many scenes other than those actually depicting oral aggression or symbolising oral sexuality. For Goya, to a degree unknown in any European artist before him, habitually relies on the mouth to convey the passion possessing a figure. With other artists facial expression is conveyed by the face as a whole, and by the eyes to more or less the same degree as the mouth. With Goya the mouth dominates the face - and not only the face but the whole body. For, after all, in general painters and sculptors of figure-subjects do not depend primarily on facial expressions to convey the passions animating their actors. Their actors, like actors on a stage who know that their facial expressions are hardly visible beyond the front rows of the stalls, must convey their passions through the gestures of their whole bodies. Goya, however, tends to restrict the body's expressive role. "His figures have the jerky movements of puppets, not the expansive actions of heroes. After the eloquent decisive gestures of that long chain of great European figure-painters from Giotto to Tiepolo and David, Goya's gestures, suddenly - apart from the gestures of his mouths - are ambiguous. Here gesture loses the clarity of a language, and the language of flat shape takes over the main burden of conveying meaning. In a Goya drawing of, say, two men fighting, the drama lies less in how they are seen to act in relation to each other than in the expressiveness of the configuration which their combined forms establish on the page. "And Goya uses every pretext to present his figures, not as articulated bodies, but as looming shapes, which are as eloquent in their silhouettes as they are mysterious in their identity and often their actions. There are those menacing silhouettes of shadowy figures which - especially in the prints - loom up in his backgrounds. There are his crowds, which are not a multiplicity of individuals but - even when near to the eye - a sea of faces and bodies in which separate identities are submerged. Above all, there is his use of cloak and cowl. Goya uses drapery, not as other artists use it, as a foil to the free action of the limbs and to the texture of flesh, but to disguise, to submerge, to depersonalise. "The prototype of the recurrent cloaked and cowled figure appears in Plate Three of the Caprices, looming up, its back to us, over a mother and a pair of terrified children. The caption is 'Here comes the bogeyman', and Goya's gloss reads: 'Lamentable abuse of early education. To cause a child to fear the bogeyman more than his father and so make it afraid of something that does not exist.' The nameless draped apparition is more potent in the children's eyes, more real, than their father, a mere person, could be. And so it seems to have been for Goya: again and again he embodies menace or aggression in a nameless looming hulk - and this in realistic as much as in fantastic scenes, so that in The Executions of the Third of May, 1808 the firing-squad, their backs to us, are not men but massive threatening shapes, and the face and pose - the outflung arms - of the next victim precisely echo the face and pose of the child nearest the apparition. "The Renaissance-Baroque tradition in painting is essentially about the human figure acting in space. Not only is man the summit of natural beauty; he is the vehicle of all life. So the human figure is shown enacting the feelings and emotions the image is intended to convey, and representations of it acting are sufficient to embody - as the Olympian gods do - abstractions such as love and war and folly and fear, whereas in many artistic traditions passions and ideas are transmitted through a language of symbolic forms. Goya finds ways to deny the human figure that heroic role. The one area of his mature work in which the most eloquent thing about his figures is their actions in space is the bull-fighting prints - the most commercial of his subject-pictures - and here, by way of compensation, he makes it fairly plain that for him the hero is the bull. "In spite of all he owes to Rembrandt and Velázquez, and in spite of his being a highly visual painter, the dramatically telling attributes of his subject-pictures tend to be attributes characteristic of primitive and archaic art-forms - the suggestive eloquence of impersonal shapes and the vivid representation of an isolated organ of the body; and also the creation of hybrids of man and beast. Goya here has an intense obsession and a fertility of invention which set him apart from other European painters. "Yet there is still, surely, The Naked Maja as an affirmation of the Renaissance tradition's cult of the human body? It celebrates the sexiest skin, the most resilient flesh, the most exquisite suggestion of a line of hair running from the navel down. But the incoherent articulation - the inexplicable incompetence of the drawing of the arms, the impossible position of the breasts, the unconvincing conjunction of the head with the neck - is a virtual denial of the Renaissance tradition's feeling for the body as a functioning whole, not an assemblage of delicious parts. Goya sees his nude as he sees the women in his portraits - as a doll. "His space, moreover, has nothing of the plenitude of Renaissance and Baroque space. It is airless, depthless, cramping, oppressive: it precludes the very possibility of heroic action. It is full of flying figures. Titian's figures in flight are solid bodies borne up by the marvellous buoyancy of the space, a space invested with an energy which counteracts gravity. Goya's space is a lifeless void; the figures float because they have no density. All his figures are weightless: their feet placed on the ground, they do not so much stand on it as brush it, like marionettes. The space is like space in dreams, the figures like figures in dreams. The fantastic scenes become nightmarish because they have the quality, the atmosphere, of dreams. And the royal portrait group, say, no less than the witches' sabbaths, appears to be happening in a dream..."

See more