Marc Franz

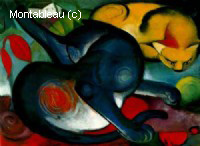

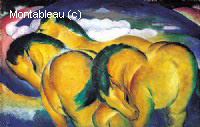

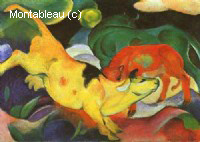

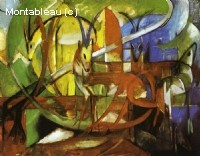

Franz Marc, whose career was cruelly cut short by the First World War, has in recent years been the most popular of all the German Expressionists. One reason for this is supplied by his eloquent and touching letters. Another may be the fact that his work is not very typical of Expressionism as it is generally understood. He found a way of giving the German Romantic painters - Runge, Friedrich, Kobell, Blechen, Rethel and Schwind (all of whom he warmly admired) a new and modern guise. Marc was born in Munich in February 1880. His father, Wilhelm Marc, was a professional landscape painter. His mother, a strict Calvinist, came from Alsace, but had been brought up in French speaking Switzerland. Marc himself was a serious child, perhaps because of the repressive influence of his mother. In high school, his plan was to read theology, but he eventually enrolled at Munich University as a student of languages. In 1900, however, when his year of military service was over, he decided to follow in his father's footsteps and become a painter. He enrolled at the Munich Academy of Art. in 1903, with the first stage in his training completed, Marc went to Paris, where he spent several months, also visiting Brittany. He was greatly excited by his discovery of the Impressionists at the Durand Ruel Gallery and in letters home proclaimed them to be 'the only salvation for us artists', but they made little visible impact on his work. When he returned home he entered a state of deep depression with an 'anxiety that numbed the senses'. This was temporarily cured by a trip which he made to Salonika and Mount Athos in the spring of 1906, accompanying his brother, who was making a study of Byzantine manuscripts, but returned as soon as he got back to Paris. He tried to alleviate his condition by drowning himself in his work, but knew he was getting nowhere. He also got engaged to be married, which he regretted, and only disentangled himself by running away to Paris the day before the marriage ceremony, at Easter 1907. Once back in Paris, he was again entranced by the Impressionists. In a prophetic metaphor he said that he walked among their paintings 'like a roe deer in an enchanted forest, for which it has always yearned'. He also discovered the work of Gauguin and Van Gogh, and was impressed by the latter in particular. He declared that his own 'wavering, anxiety ridden spirit found peace at last in these marvellous paintings'. It was at this period that he began the intensive study of animals which was to lead to his mature style. He said that he wanted to recreate them 'from the inside', and made himself so complete a master of animal anatomy that he was able to give lessons in the subject, until igio, in order to earn some money. Though he felt he was now making some progress, he destroyed his more ambitious works, as they continued to dissatisfy him. In December 1908 he wrote a letter to Reinhart Piper: I am trying to intensify my feeling for the organic rhythm of all things, to achieve pantheistic empathy with the throbbing and flowing of nature's bloodstream in trees, in animals, in the air. The year 1910 marked a significant turning point. In January he met August Macke, a painter seven years younger than him, but who seemed extremely sophisticated and well informed. Through Macke he learned something of the Fauves, and the following month was able to see what they were doing for himself, thanks to a Matisse exhibition in Munich. Macke also introduced him to the collector Bernard Koehler, who happened to be the uncle of Macke's wife. Koehler liked his work, and offered him a monthly allowance, which removed the worst of his financial worries. In September Marc defended the exhibition of the Neue Kuenstlervereinigung, which was being attacked by the local Munich critics, and was offered membership of the group as a result. He did not, however, meet Kandinsky, its leading spirit, until February 1911. By that time he had formed his own set of artistic principles, which were a mixture of Romanticism, Expressionism and Symbolism. In December 1910 he wrote a famous letter to Macke, assigning emotional values to colours: Blue is the male principle, astringent and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, gay and spiritual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy and always the colour to be opposed and overcome by the other two. In 1911 he found himself ready to embark on the series of paintings of animals which have since been the cornerstone of his reputation. And in December, after a split in the Neue Kuenstlervereinigung, organized the first Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) exhibition. Formerly so ineffective and depressed, Marc had now become a most efficient organizer, and it was he who persuaded the publisher Reinhart Piper to bring out Kandinsky's fundamental text, On the Spiritual in Art, and he also played a leading part in the creation of the Blaue Reiter Almanach and the organization of a second and more ambitious Blaue Reiter show in 1912. In 1913 he took an important role in selecting and hanging Der Sturm's First Autumn Salon in Berlin, and noted how many of the exhibitors were veering towards abstraction. This confirmed his feelings which had begun to emerge when he and Macke went to Paris to visit Delaunay in 1912, and saw some examples from the latter's Window series. By the spring Of 1914 Marc's own work had become virtually abstract. This promising career was cut short by the war. Marc was mobilized and wrote numerous letters home from the Front, expounding his aesthetic philosophy, and kept a notebook with drawings for the paintings he would create as soon as he was free to do so. But he was denied the opportunity he hoped for. In March 1916 he was killed instantly when he was struck in the head by a shell splinter. From Edward Lucie-Smith, "Lives of the Great 20th-Century Artists"

See more